Not just a musician – and the Surprising Rebirth of Belief in God

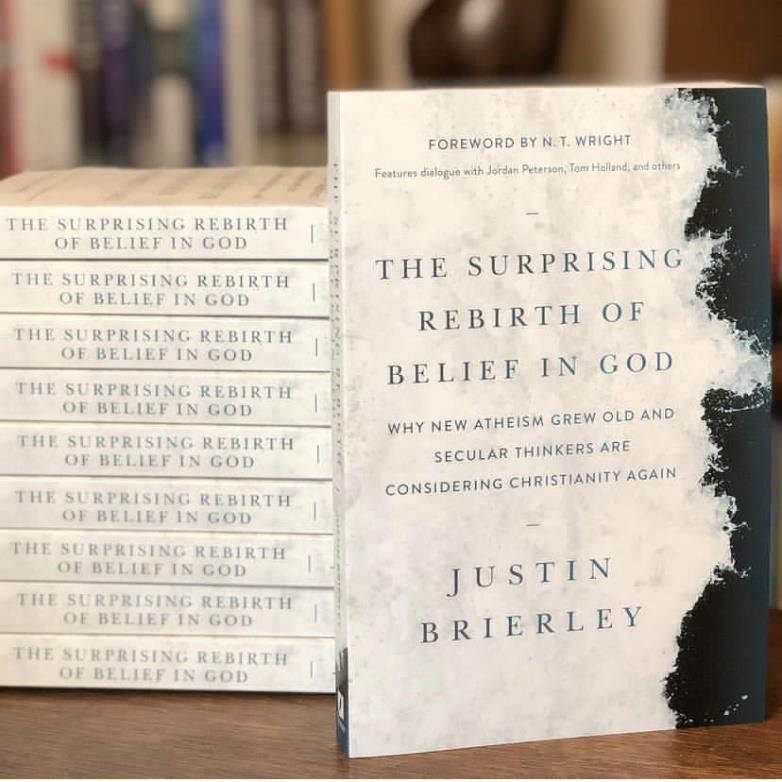

Dear Friends, Many of you know that our family spent time in the USA this summer. What you may not know is that the reason for this was that Justin was embarking on a speaking tour to promote his new book – The Surprising Rebirth of Belief in God: Why New Atheism Grew Old and Secular Thinkers are Considering Christianity Again. Justin’s first book – Unbelievable? Why after 10 Years of Talking with Atheists I’m Still A Christian – was published in 2017 by SPCK. This time he is working with the US publishers Tyndale, as well as using SPCK for the UK distribution. Justin’s work in Christian Apologetics has gained him an audience all over the world, but most especially in the USA. The recent book was launched in the USA this summer and released here on 26th September.

For us as a family, it was fun to support him on his speaking tour in universities and churches in Minnesota and South Dakota in August, and by the time this article is published, he will have just returned from another trip to Florida and Texas. When I was present, I found it very moving to meet people who have been drawn back to God, or even found faith for the first time, as a result of his work. Below is an article about the contents of the book which Justin recently wrote for the Church Times. I hope you will find interesting in gaining an insight into the world he inhabits when he’s not playing guitar or helping with other things at Woking URC!

Lucy

The Surprising Rebirth of Belief in God, by Justin Brierley

A peculiar thing happened in 2009. Atheists started to advertise God on the sides of London buses. Naturally, the adverts weren’t positive. The posters read ‘There’s probably no God. Now stop worrying and enjoy your life’. But I was thrilled that atheists were raising the God question at all among a general public that was largely uninterested in religion (as well as leaving the question tantalisingly unresolved by the use of the word ‘probably’).

The atheist bus campaign represented the high watermark of a wider phenomenon dubbed ‘New Atheism’. This unabashedly activist form of anti-theism commanded much sway in popular culture by arguing that belief in God was irrational and decrying religious practise as immoral. Its so-called ‘four horsemen’ – Sam Harris, Christopher Hitchens, Daniel Dennett and Richard Dawkins – had each published bestselling anti-God books and were feted at atheist conferences and across its sprawling blogosphere. New Atheism’s rallying cry of ‘science and reason’ appealed to intellectually-savvy millennials who were looking for a cause to rally around.

Yet, ten years later, New Atheism had faded from view almost as quickly as it arose. This was partly because the public lost interest (indeed, it has started to look suspiciously religious to many onlookers). But the movement also unravelled internally. Once its adherents had agreed that God did not exist and religion was bad for you, it turned out they couldn’t agree on much else.

Fractures began to appear when feminists within the movement questioned why it was being led by a phalanx of straight, white men, some of whom had been accused of sexually inappropriate behaviour. Progressives advocated for ‘Atheism +’ adding feminism, LGBT, race and other social justice issues to their cause. Others were appalled at the idea of (in their view) politically-correct ideologies overtaking their movement for science and reason. Squabbles turned into outright warfare as atheist leaders began to fall out with each other. Richard Dawkins ended up receiving more grief for his controversial tweets from secular peers than he ever did from religious people. It was the culture wars that ultimately sank the New Atheism.

New Atheism had sought to tear down the last vestiges of the Christian story that once gave shape to people’s lives. But, by failing to erect anything meaningful in the place of God, the movement itself died. Science and reason are great for some things, but they won’t buy you a meaningful life.

However, in the wake of the movement dissipating, I have witnessed a new set of secular thinkers stepping onto the stages and platforms that once hosted the four horsemen. They seem to be drawing the same crowd of intellectually-curious Millennials (and now Gen Z), but with a big difference. They aren’t dismissing God.

A prominent example is Jordan Peterson, the popular Canadian psychology professor. While his ‘anti-woke’ views tend to get him labelled as a right-wing political pundit, when he addresses audiences of predominantly young men (and he will be packing out London’s O2 Arena in November) he will speak for up to 3 hours on the way Biblical wisdom can give meaning and purpose to life’.

Louise Perry, author of ‘The Case Against the Sexual Revolution’ is a similarly intriguing character. As a secular women’s rights advocate her own intellectual journey has led her to embrace increasingly Christian conclusions that chastity and monogamous marriage are the best model for sex and relationships that we’ve ever devised.

Historian Tom Holland, who co-hosts the popular ‘Rest Is History’ podcast had his secular assumptions steamrollered when he began researching and writing about the ancient world. In recognising how alien the values and practises of the Greeks and Romans were to his own belief in equality, freedom and human rights, Holland realised his moral instincts stemmed directly from Christianity. He has been reminding his secular peers about it ever since in best-selling books such as ‘Dominion: How the Christian Revolution remade the world’.

These and other intellectuals are part of a movement I have termed ‘The Surprising Rebirth of Belief in God’. These thinkers may be at different places in terms of personal faith, but they are all talking about Christianity as an intellectual option for thinking people. And I have met many individuals who have walked through the door they’ve opened. Whether it be my friend Dean, a former-atheist-turned-spiritually-curious-agnostic who now attends church, or Oliver, a former agnostic, who, after discovering this new world of religiously-open thinkers, has recently entered training for Anglican ministry, the atmosphere has changed.

Time will tell whether such trends in popular culture can stem the secularisation of the West. God knows if the church would be ready for an influx of refugees from the meaning crisis. But I believe the tide is going out on the atheist worldview and the returning ‘Sea of Faith’ may yet be able to bring the Christian story back to our shores.